Public Relations in a Hyper-Connected World

Public

Relations in a Hyper-Connected World

Written by Grace McGregor

30/05/25

The public relations profession, often misunderstood and at

times maligned, stands at a crucial juncture in the 21st century. As the world

continues to grow and evolve, contemporary PR practitioners navigate a complex

landscape shaped by rapid technological advancements, evolving media

consumption habits, and an increasingly discerning global public. This blog

post will critically analyse five core concepts within public relations through

a theoretical lens, demonstrating their practical application in today's

hyper-connected world.

|

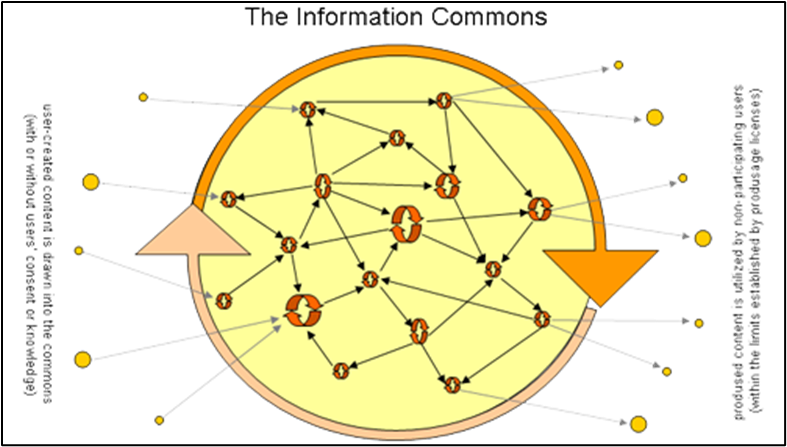

Figure 1: Produsage Diagram |

Jürgen Habermas's concept of the public

sphere envisioned a space for debate, ideally fostering informed public opinion

For instance, consider the impact of X (formerly Twitter)

during a major news event. While it can facilitate immediate information

sharing and foster collective action, it also becomes a breeding ground for

rumour and unverified claims

The agenda-setting theory, posited by Maxwell McCombs and

Donald Shaw, suggests that the media doesn't tell us what to think, but rather

what to think about

Take, for instance, the spread of health information during

a pandemic. While reputable news organisations report on official guidelines,

algorithms on social media might inadvertently amplify misinformation or

alternative viewpoints, based on user engagement metrics rather than factual

accuracy

George Gerbner's cultivation theory argues that prolonged

exposure to media, particularly television, shapes our perceptions of reality

Framing theory, as explored by scholars like Erving Goffman

and Robert Entman, suggests that the way information is presented, or

"framed," significantly influences how it is interpreted by an

audience

Think about the

differing frames used to describe economic policies. One political party might

frame a tax cut as "stimulating the economy and creating jobs," while

an opposing party might frame it as "benefiting the wealthy at the expense

of public services." Both might be factually accurate in their

descriptions, but the chosen frame elicits distinct emotional and cognitive

responses. In public relations, this means carefully selecting language,

metaphors, and visual cues to present an organisation or issue in a desired

light

Figure 2: Framing Theory in Action |

Everett

Rogers's diffusion of innovations theory explains how new ideas, practices, and

products spread through social systems

Consider the rapid adoption of contactless payment systems

or electric vehicles. Public relations campaigns for such innovations don't

just target a broad audience; they strategically aim to influence different

adopter categories

The public relations profession in the global media

landscape is undeniably dynamic and multifaceted. As demonstrated through the

critical analysis of the public sphere, agenda-setting, cultivation, framing,

and diffusion of innovations, PR practitioners must possess a sophisticated

understanding of communication theories to effectively navigate the

complexities of contemporary global media and communication. Beyond publicity,

successful public relations in the 21st century demands a

theoretical grounding that informs strategic engagement, fosters genuine

dialogue, and contributes to shaping a more informed and engaged public.

References

Anderson, A. (2009). Media, politics and climate

change: Towards a new research agenda. Sociology Compass.

Bruns, A. (2018). Gatewatching

and News Curation: Journalism, Social Media, and the Public Sphere.

Chadwick, A.

(2013). The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power. Oxford University

Press.

Chong, D. &.

(2007). Framing theory. Annual Review of Political Science.

Dearing, J. W.

(2018). Diffusion of Innovations Theory, Principles, and Practice.

Health Affairs.

Entman, R. M.

(1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal

of Communication.

Gerbner, G. G.

(2002). Growing up with television: Cultivation processes. Media

Effects: Advances in Theory and Research.

Gillespie, T.

(2014). The relevance of algorithms. Media Technologies: Essays on

Communication, Materiality, and Society: MIT Press.

Goffman, E.

(1974). Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience.

Harvard University Press.

Greenhalgh, T. e.

(2004). Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic

review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly.

Habermas, J.

(1989). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into

a Category of Bourgeois Society. MIT Press.

MacLeod, A. (2020,

September 3). Great example of how powerful media framing can be.

Retrieved from X: https://x.com/AlanRMacLeod/status/1301275702755504129

Matthes, J.

(2009). What's in a frame? A content analysis of media framing studies in

the world's leading communication journals. Journalism & Mass

Communication Quarterly.

McCombs, M. E.

(1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion

Quarterly.

Morgan, M. S.

(2015). Yesterday’s new cultivation, tomorrow. Mass Communication and

Society.

Napoli, P. M.

(2014). Automated media: Algorithmic media production and the case of the

narrative science. Digital Journalism.

Papacharissi, Z.

(2002). The virtual sphere: The internet as a public sphere. New Media

& Society.

Produsage.org.

(2002, January 2). Picturing Produsage. Retrieved from Produsage.org:

https://produsage.org/node/13

Rogers, E. M.

(2003). Diffusion of Innovations. Free Press.

Tandoc, E. C.,

Lim, Z. W., & Ling, R. (2018). Defining ‘Fake News’: A typology of

scholarly definitions. Digital Journalism.

Tufekci, Z.

(2015). Algorithmic harms beyond Facebook and Google: Emergent challenges

of computational agency. Colorado Technology Law Journal.

Wejnert, B.

(2002). Integrating models of diffusion of innovations: A conceptual

framework. Annual Review of Sociology.

Comments

Post a Comment